Why Can't They Just 2—Understanding the High Expectations to Disappointment Cycle

ARTICLESCORPORATE CULTURELEADERSHIP

Sarah Kesher

Installment 1 can be found here.

Note: I’ll use “team member” throughout this installment, but that could mean an employee, contractor, intern—really anyone you rely on to help get the work done.

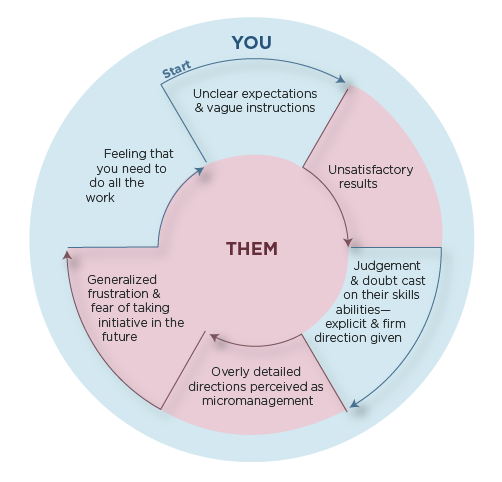

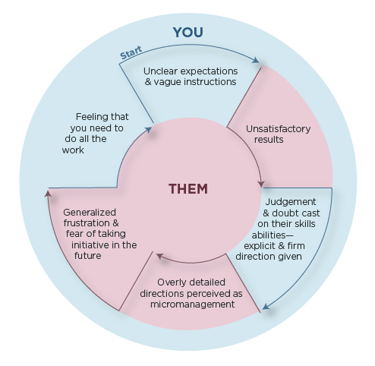

In the last installment, we touched on the High Expectation to Disappointment Cycle. Before we move on to how to address this challenge, it's worth diving a little deeper into the cycle itself. I find that it's one thing to look at something like this and say "yeah, yeah. I get it" but it's something else to thinking about how it connect to your own behaviors and those you see around you. So, as a refresher, here's the cycle again.

Was the work wrong? No. Was it what you meant? Also no.

©2025 Sarah Kesher Consulting, L.L.C.

And, this is how it tends to play out in most organizations:

It starts with hope.

Whether it’s the first time you’re working with this person or the tenth, there has to be a spark of hope that they’ll be able to handle what you’re asking. That spark may be faint if you’re deep in the cycle already, but if it was gone completely, you’ve probably already stopped trying to delegate anything.

For a new team member, the hope (a.k.a. expectations) might sound like: > “We brought this person in because they can really take our ____ to the next level.”

For an established team member, it might sound like: > “At this stage, they should be able to handle this.”

The Grandiose Obfuscation of Semantically Ambiguous Yet Ostensibly Directive Communications

(aka: You said stuff. Nobody knows what you meant.)

Your hope has convinced you to hand over the assignment. You see the end product clearly in your mind. You know what you’d do, the tools you’d use, the outcome you expect. So you say:

“Can you put together a quick presentation for the meeting on Monday showing our Q2 results?”

You think you’ve been clear. After all:

Monday = the exec meeting. “Everyone” knows that.

No more than 2 slides—execs don’t do long decks.

Focus on financials only because, execs.

Clean, visual layout preferred.

It’s Tuesday now, so obviously you’ll need it by EOD Thursday to finalize on Friday.

But here’s what happens:

It’s 3 p.m. Thursday. You haven’t seen anything. You ping the team member. They’re halfway done—they didn’t know you needed it before Monday. You get it Friday at noon:

10 slides Includes marketing and survey data

Densely written and at too basic a level for execs

No charts or graphs in sight

Uses an “official” template you happen to loathe

Was the work wrong? No. Was it what you meant? Also no.

Heavy sigh. Cue disappointment.

Now you’re frustrated. You’re under a time crunch. You start thinking, “This would’ve been easier if I’d just done it myself.” And maybe you say it. Or maybe it just stews. But either way, that moment—that question—plants a seed of doubt:

Can I really trust this person to deliver next time?

Here’s where the cycle can get especially corrosive: when “the work isn’t right” becomes “you aren’t right.” It’s a subtle shift, but a dangerous one. Maybe it shows up as a tone shift or a sarcastic aside, but the message lands: *What’s wrong with you?” That’s where shame enters the room.

And once shame takes hold, it’s not just trust that gets corroded. It chips away at the team member’s confidence. It causes embarrassment. It creates self-doubt. We’re talking about the corrosion of psychological safety, a basic workplace need. It shuts down the very things that allow people to add real value to their organizations—the willingness to take risks, think creatively, and stay meaningfully engaged. These aren’t soft skills or nice-to-haves—they’re the very thing organizations claim to value most.

If that person has options, they’ll likely leave. If they don’t, they may stay, but only in body. They’ve mentally checked out and stop showing up in all the ways that matter.

They’ve stopped showing up in all the ways that matter.

From clarity to control

So next time, you give direction again, this time more explicitly. But not helpfully. More like instructions written in permanent marker on a whiteboard. Your “feedback” turns into a step-by-step to-do list. It’s not just what you want done, it’s how, when, where, and with which font. The team member is now executing, not contributing.

You justify it. “I don’t have time for another redo.”

From initiative to fear

Your team member sees the writing on the wall. They tried to show initiative and it backfired. So now they ask, “How would you like me to do that?” Over and over. Because the safest bet is to follow your preferences to the letter. No surprises = no disappointment.

Back to you

Now you have someone who doesn’t offer ideas, doesn’t take initiative, and won’t lift a finger without your approval. And you’re thinking, “Why do I even bother?” But also, you can’t do it all yourself. So you try again.

Rinse. Repeat.

The Culture Catch

What makes this cycle so sneaky is that it feels logical in the moment. You had high standards. They didn’t meet them. You pulled back trust. End of story, right?

Except…that logic only works if your expectations were actually clear, realistic, and shared. And more often than not? They weren’t. It's this logic that brings you right back to where you never wanted to be: doing everything yourself.

Coming Up Next: Installment 3: The Engagement Model – A Way Forward

We’ll break down a practical, repeatable approach to prevent this cycle before it even starts — and show you how to set expectations that actually stick.

#LeadershipDevelopment #EmployeeEngagement #OrganizationalCulture #WhyCantTheyJust